Landforms and Processes

Geological work by HSP shows that the Sistan Depression is much older than traditionally characterized, somewhere in the neighborhood of 3-4 million years. The interactions of the Eurasian plate in Iran with the Afghan microplate created the important and active Sistan Suture, and the migration off the Indian plate northward produced the active Chaman Fault in eastern Afghanistan that forms the western boundary of the Indian plate. The south edge of Sistan and the Helmand Basin was formed by the northward accretion of the Makran thrusts in western Pakistan.

Volcanic activity, a byproduct of the clash of continental plates, created a chain of volcanoes in southeast Iran, the Chagai Hills in Pakistan, and Koh-i Khan Neshin along the Helmand River. These volcanic locations help to identify relative ages of basin deposits that woefully lack direct dating by modern radiometric and isotopic techniques. Recent isotopic dating of the Afghan volcano indicates volcanism began about 3.8 million years ago and suggests that age for the top of the basin fill below the Dasht-i Margo. Other late Tertiary volcanic extrusions are found along the Sistan Suture at the western edge of Sistan, including the famous Koh-i Khwaja in the Hamun-i Helmand, where archaeological sites of several periods are found.

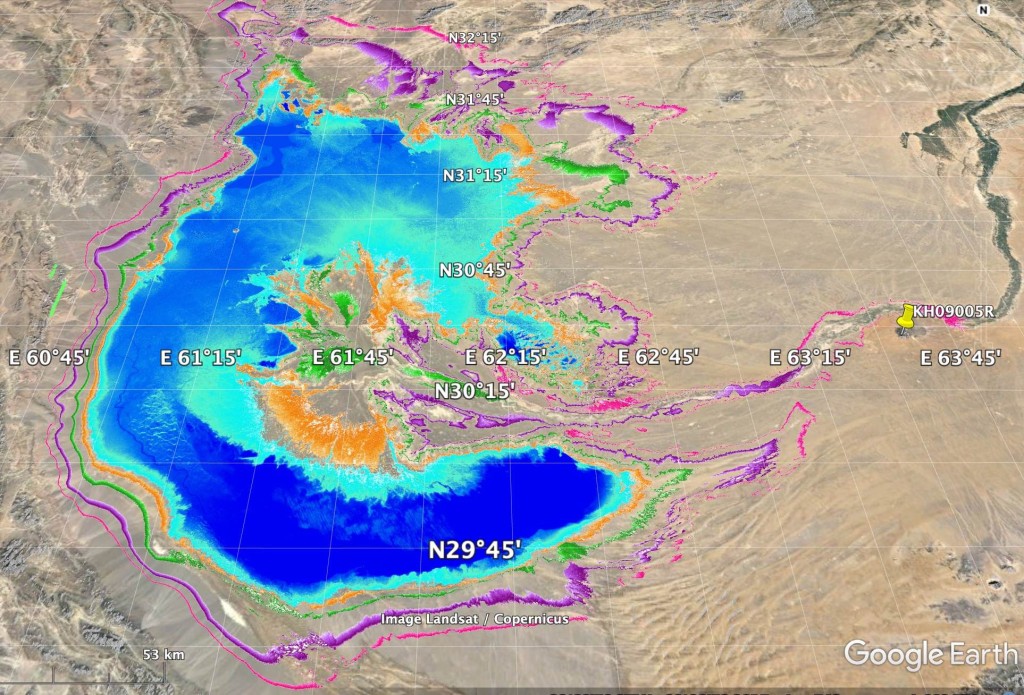

The complicated interactions of these tectonic forces has resulted in the dramatic subsidence of the Sistan Depression, the original level of which is now below sea level under 2 km of lakebeds that have accumulated in the area of the western hamuns.

The strength of the modern and ancient winds has had an important role in shaping and excavating the Sistan Depression. This has been suggested by most previous investigators over the past century as the most effective geomorphic process for expanding and deepening this basin. With the exception of hamuns when they contain water, most land surfaces in Sistan are impacted by wind erosion or by deposition of blowing sands. The formerly inhabited Sar-o-Tar Plain has been scoured by these winds which expose older canals, irrigated fields, house foundations, and cemeteries. Winds also created exotic landforms, such as yardangs, found in several locations around Sistan, where pillars of soil were left standing with the soil all around them blown away. In some cases, the tops of these yardangs contained artifacts, which allowed us to project the speed with which the soil around these yardangs were blown away. The larger fields of yardangs are believed to have been created during the cooler, drier, and windier conditions of the last Pleistocene glacial episode. Winds were also responsible for building and moving sand dunes.