The Land

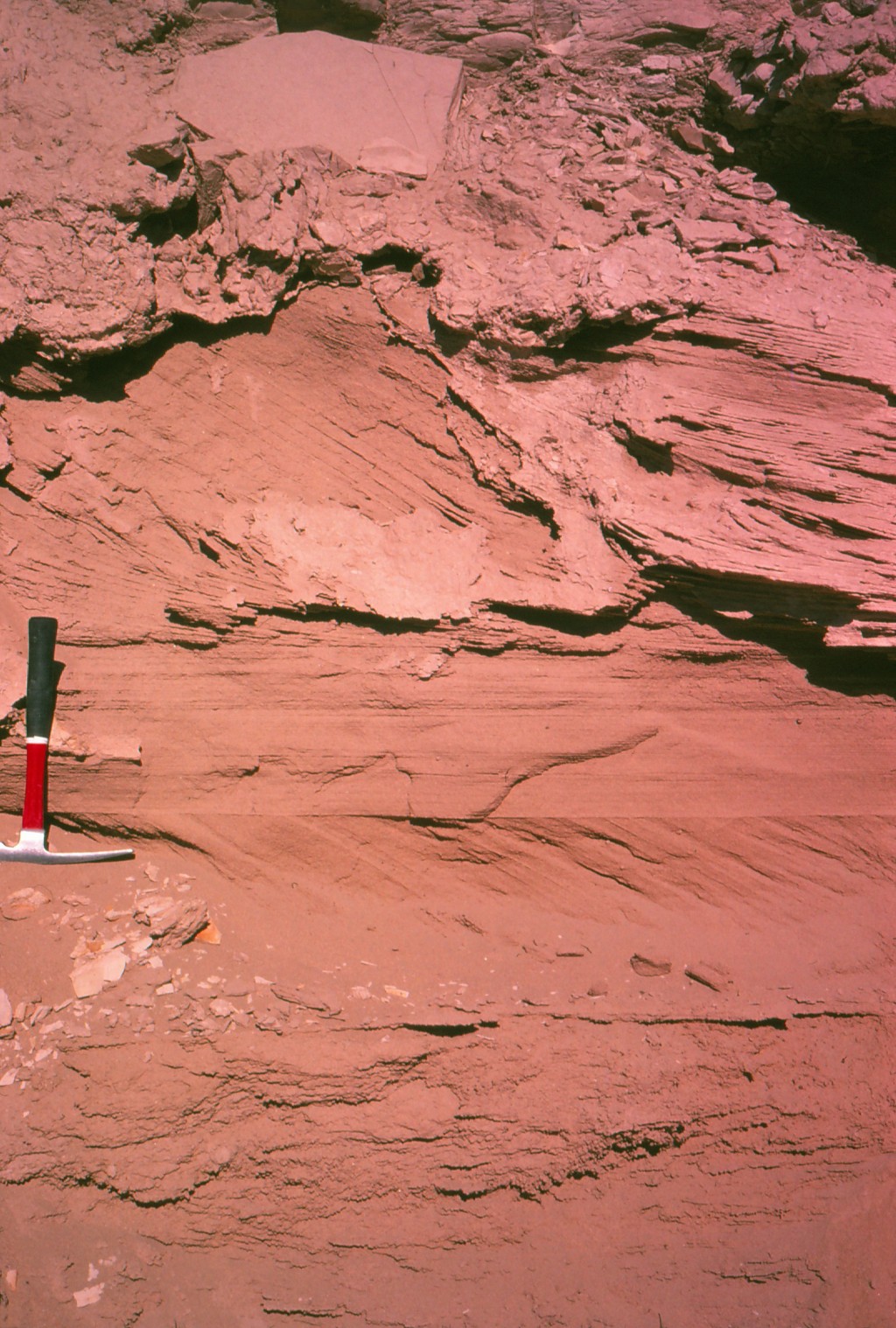

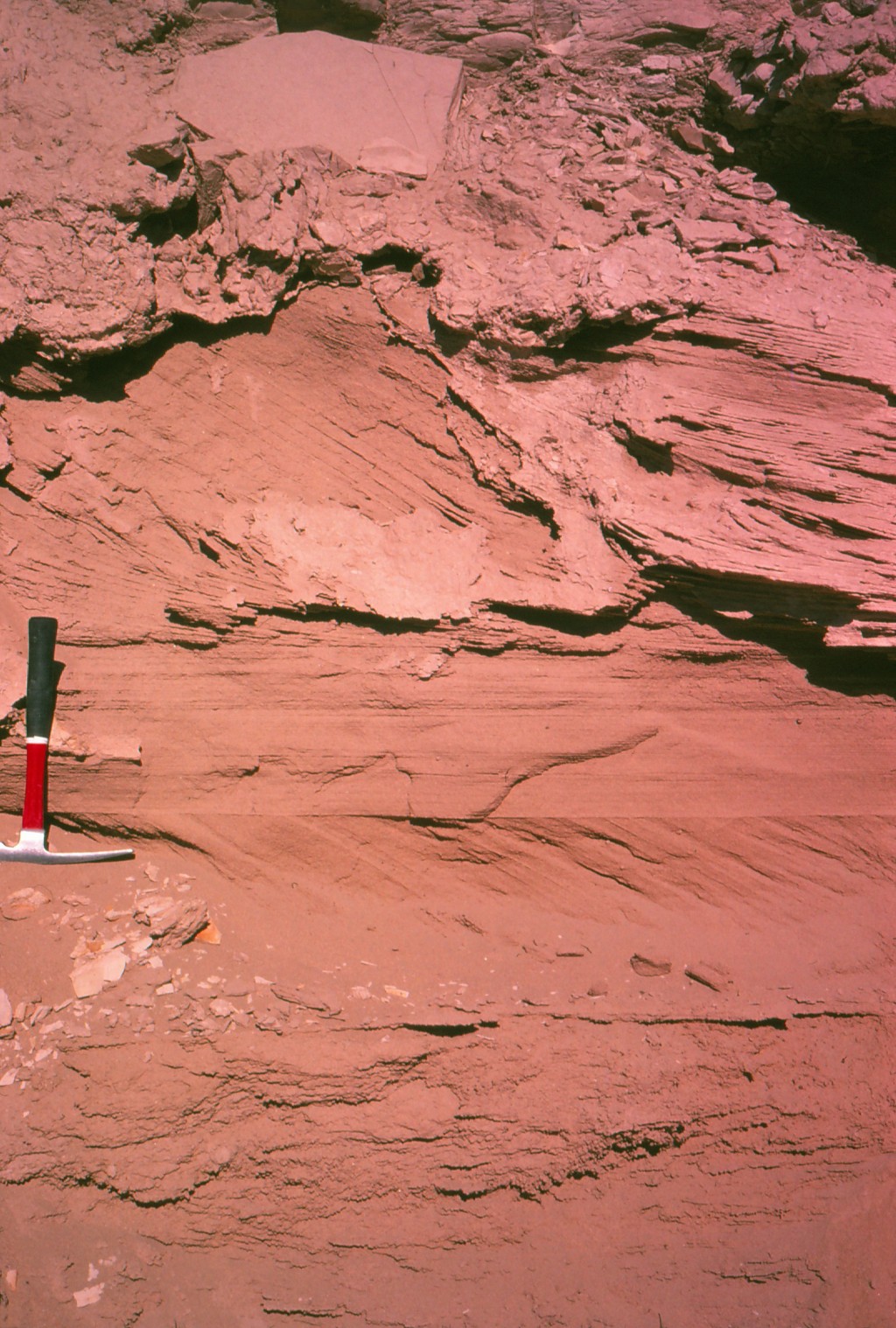

The steady winds from the northwest have had enormous impact on the landscape, sandblasting everything in its path, especially during the summer Wind of 120 Days.

The steady winds from the northwest have had enormous impact on the landscape, sandblasting everything in its path, especially during the summer Wind of 120 Days.